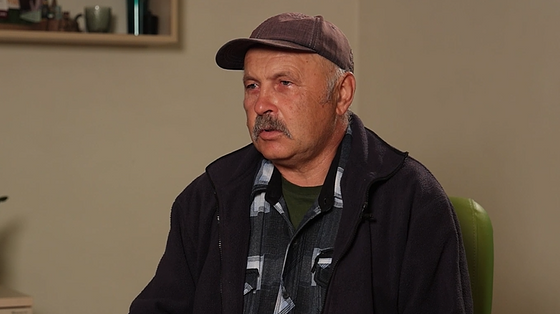

Before the war, Kostiantyn and Vlada Liberov were not just engaged in photography, but they rather lived in photography. Their main characters are people and all the best in them. Love stories, vivid and true-to-life portraits, and genuine feelings.

When the war began, the Liberovs continued to do what they love – taking photographs of people. But now the main characters of their works are residents of the hottest war spots. Mykolaiv, Kharkiv, Chernihiv, Sievierodonetsk, Irpin, Bucha…

Kostiantyn and Vlada Liberov told the Museum of Civilian Voices about Ukrainians in the war, about the tragedy, fear and faith in victory.

We were at home in Odesa. The day before that we met with our friends. It just so happened that our friends are not in Ukraine now. It so happened that we had a chance to say goodbye to them because the last time they visited us was at our home. We spent some time together and then we went to bed. No, we did not go to bed. First, on 23 February, on the night of 23rd to 24th February, to be more precise... Usually Vlada is not like that, but at that time she had a little fit of hysterics on the question, “Kostya, what if the war begins and we are not ready? What should we do?” So she had a bit of a tantrum.

I just had uncontrollable tears for an hour. I could not do anything about it. Just for no reason. It was a few hours before the first explosions.

We went to bed and I kept soothing Vlada all the time, “Vlada, what kind of war can it be in the centre of Europe? Well, do you really believe in what you are saying? It cannot happen.” A few hours later, he woke me up with the words that the war began. We packed up almost half of our apartment, loaded it all into the car, took our dog, and took a bed for our dog too. We loaded it all into the car and went to pick up our parents.

My parents are mature and serious people, and my dad said that he would be shooting back with a rifle, but he would not leave the house. My mum said she would not go without her sister, and sister would not go without my mum. So there was a kind of a chain reaction the result of which was that no one was going to leave.

Our next move was – ok, no one is coming, but we will go to Europe to earn money, to provide for you, provide for the family. Then we spent half a day at a fuel station; then we withdrew some cash, and after that, when we were done with all these preparatory processes...

We ourselves are from Odesa. It would normally take us an hour and a half to go to Moldova, to the border, well, even less. But at that time people stood in waiting for days, although it is very close. So when we finished all these preparations, we looked at each other and went home. That is, when we were ready to leave, when we could leave, we then realized that we would not be able to do it for another reason. We just could not leave [physically]. We engaged in volunteering in Odesa then. We drove from point A to point B by car, transporting or delivering something, and we had a mission too. It was cold then and all our guys who were on duty at checkpoints needed to have warm clothes. So we raised some money, found some necessary items, and some fabrics.

There were some local suppliers of thermal underwear, but no one could find thermal underwear for the guys and for the AFU (Armed Forces of Ukraine), as well as the territorial defence units. We distributed over a thousand sets of thermal underwear. In fact, before the war, we were engaged in... Kostya is a photographer and I am the director of photography. We taught people photography, we shot love stories, shot weddings, and that was our life. This is not just a source of our earnings. This is our life. We are constantly engaged in this all. And after a couple of weeks, I was afraid that photography would leave our lives, and it so happened that the next day we... we were supposed to bring something to the railway station. I came there and waited for Kostya. While waiting, I managed to catch some kind of a subversive reconnaissance group’s agent and hand him over to the police. It was some suspicious man. Kostya came and said, “I took some pictures.” We published them and realized that there is still a place for photography in our lives, and everything that happens needs to be documented.

We came to Mykolaiv on 14 March and saw the first shelled city districts, Solyani district. Several cluster bombs landed there and there were some first victims. It was told that people stood in a queue at ATB food store when a cluster bomb hit, which is a prohibited type of weapon. Nine people died.

These were the first victims in Mykolaiv city. Men were standing near their cars and the cars were just riddled. There was a complete lack of understanding in those men’s eyes, “What should I do? Where to take it to be repaired?”

First damage stories. After Mykolaiv, we went to Kharkiv.

For the first time we saw people who live in basements. Before that, we only heard that people live in basements. The picture was just horrendous.

Well, anyway, you cannot understand it until you go down there and get the sense of it. We went to the Northern Saltivka district where we came under shellfire. We were with volunteers who brought some anti-tank hedgehogs. We saw that the whole group was spotted from a drone. We managed to run inside a building in 20 minutes and accurate mortar fire started. It was scary. I was afraid for Vlada. I thought about how to cover her. If the building had started to collapse, nothing would have helped there.

We heard a whistling sound and someone shouting, “Run inside right now!” We ran, we did not understand what’s going on. Here it starts... you run inside, fall down and keep lying on the floor. We didn’t have time to run to the basement. We were on the ground floor. You just lie there, while everything is shaking. It is very loud and you wait until it calms down.

And that’s it, like in movies, you run crouching, jump into the car, the wheels slip, like in a movie, and it takes off. You are driving and you see through the window: one building is on fire, and another one... Now I understand that we could have taken pictures of those burning buildings, but at that time, we were just scared. We have a photo in the basement with locals.

I took a picture of one poor man. We met a man who organized a living space just in the basement of a kindergarten. People went down there to live in some technical premises. There were some pipes and nothing else there. People went down to live there, and he was just a man who had nothing to do with the kindergarten, but he arranged the living space there and even set up a toilet. It was dark there. There were children and old people, everyone was there. There are still people living there.

You walk through and see it like a post-apocalyptic picture. For example, an apartment that is all covered with stalactites of ice because the water pipe broke. It’s a frightening sight, to be honest with you. There is Northern Saltivka district that is under heavy shelling and there is also a similar Horizon district. It felt like there was some tension in the air. Nothing [visible] was happening there, but there was some kind of vibration. Horizon district is one and a half kilometres from the front line, and further there, behind the wood line, the “orcs” [enemy soldiers] are positioned.

We saw almost a biblical scene: a guy in a helmet and with a shovel in his hands clearing out rubble from the entrance hall, while the other half of the scene shows a large icon hanging [on the wall].

And Kostya asked that guy, “What are you doing?” Five minutes ago, the area was hit [by shelling], and it will be hit more, while he, in a helmet and in a house robe, is clearing rubble out of the entrance hall. He said that for every action there is a counter-action, and just continued to clean up the trash. I dread to imagine what this man went through. He found a kind of release or mollification in clearing out the rubble in the entrance hall with his bare hands. Kharkiv got it bad. Kharkiv city gave us self-confidence and confidence about victory. We were amazed by the people who stayed there.

We realized that these people couldn’t be broken. We returned to Mykolaiv in a month. The city was left without water – people collected rainwater from puddles and from the roofs. Once it became known that Mykolaiv was without water, volunteers from Odesa started bringing tons of water to the city. Now the water supply has been restored, but at that time, it was a problem.

We then went to Kyiv when heavy fights were raging in Hostomel, Bucha and Irpin. We witnessed the last evacuation convoy from there and we saw the town immediately after it was de-occupied. People in Bucha were broken. When we tried to talk to a man, we felt he was absent-minded. He did not really want to talk to us, to talk to anyone, and we were not sure if he even wanted to breathe now. We realized that he felt a lot of pain. This is one of my hardest memories.

Then one guy took us to where he lived and behind the house he told us that this was a place where he buried his neighbours.

We also witnessed a situation with a woman in an evacuation centre… Well, she came there not to escape from Irpin and Bucha, but in order for someone to help her return to Irpin. She was told that it was not yet possible, that it was still too early. The town was not yet de-occupied. She was just standing and crying. Her house and her life were there. Yes, she survived, but every day she kept asking when she could return home.

Thousands of Ukrainians just want to return home.

One of our hardest memories is Sievierodonetsk and the people who stayed in Sievierodonetsk city. We stopped in Slovyansk and were in Kramatorsk on 11-14 April. Both Slovyansk and Kramatorsk actually turned into ghost cities by that time. What does it mean? The city authorities said that local residents should leave the cities and people left. Sievierodonetsk was heavily shelled at that time. We were told that we were lucky, as the weather was bad. We were told that they [the invaders] fired less in the rain. But we heard explosions all the time still.

At that time, many people did not leave to emphasize their position that this was their home and they were not going anywhere, and that basically everybody was firing, and so on. But this position is devoid of logic.

If the city authorities say that you have to leave, it means that it is impossible to defend the city without risking the lives of civilians. So it is necessary that civilians leave, as they would only interfere with the military. We talked to people who lived in a school gym. With small kids, several generations. We asked them, “Why didn’t you leave?” Their answer was, “No one needs us.”

We call it the project about ordinary people.

If you ask about the big or global goal of this project, it scares me that the war has left the big cities… It has left the big cities, while people in small towns are less media present or less represented in social networks. They did not stay in the social networks. At the same time, the same happens there that we described.

A small town – it is simply destroyed, annihilated, while small towns cannot raise such an outcry as residents of Kharkiv or Kyiv did. And you get a feeling that the war is on pause.

It’s like Russian propaganda. When they ask where you have been all these eight years, I really feel guilty because, for eight years, I have not cried out about Donbass, about the fact that there are Russian troops there. We just kept on living. In order for the same not to happen now, in order for it not to turn into a frozen conflict. We came to Pervomayske in Mykolaiv region. We found that the central street was damaged, completely destroyed, a hospital was destroyed too, and people were living in the basements. We brought them some medicines with volunteers. I didn’t have time to photograph anything, as we were told we needed to leave urgently.

Well, as soon as we drove off, a very intense shelling began. Artillery was just firing at the town where there were no military men, only civilians, and the latter just did not know what to do. They did not know where to go.

We met a woman who was running away from shelling, and she had her arm broken. This was 200 kilometres from Odesa. About 400 metres away, Grad MLRS rocket landed just in a field. It exploded and its fragments scattered on half of the field. And we thought, “Oh, that’s nice! Most likely, they were aiming at our car.” Maybe that is the reason why wars occur again. People forget that wars are not between politicians and generals, but primarily they concern a little man, little men’s life, in the first place. And I hope that, maybe, the photographs that we will collect will help understand that war is not statistics, but that it concerns every single person with his or her personal grief.

If, for example, Kyiv, Bucha, Irpin, these places mostly saw tank fire and small artillery fire, then Chernihiv was attacked by heavy artillery and aerial bombs. You walk around and realize that there were three houses here, but now it’s just a crater. For you to imagine an aerial bomb... Imagine a multi-story building and one aerial bomb would be like one section of the building. One section of the building is simply gone. Everything collapses and falls apart and we see that the house has no wall. This is how aerial bombs work.

On 19 April, we got a tattoo, we got it... To be honest, I never thought that I would have a tattoo. This whole war happened because there is no truth. We have a favourite phrase: everyone has their own truth. And now, in fact, the truth is so distorted. It cannot be something that everyone has in their own way. There is only one truth, and we want to be on the side of the truth, in our photographs in particular. I said that this is a war between the good and the evil. It is also a war between truth and lies, and we are on the side of truth.

I am absolutely sure that we will win because the system that putin is building is not viable. It simply cannot be. We will for sure have our new Victory Day, an official holiday, in Kyiv, a modern version of the parade. And I just dream of capturing all these emotions, smiles and kisses on photographs. I dream of making a photo that will be included in history textbooks as an illustration of Victory Day.

.png)