Artem Ilyin’s parents and brother survived in the besieged city of Mariupol against all odds. Artem’s brother managed to get out through a “green corridor” together with his family, while their parents had to come a long way from Mariupol to non-government controlled territories of Ukraine and then back to Ukraine via Russia and Belarus… Their journey from Ukraine to Ukraine lasted nine days.

The end of March and beginning of April became especially difficult. Many errands and negotiations on planning the most important trip with multiple unknowns added up to their sombre thoughts about the hometown. The travel itinerary was the so-called DPR – Russia – Belarus – Ukraine.

Together with my brother (he and his family managed to leave the city a couple of days earlier through the so-called “green corridor”), we learned that our parents are alive, that they left the besieged Mariupol on foot! That they do not have any property left, except for their two suitcases. That now we needed to take them out of that so-called DPR back to Ukraine.

In short, all that worked out just by miracle. I wrote ‘With God’s Help’ in the title for a reason. But I will not elaborate on the meaning of this phrase, as this way it will be safer for all those who helped us. Men and women from the three countries – we are infinitely grateful to you!

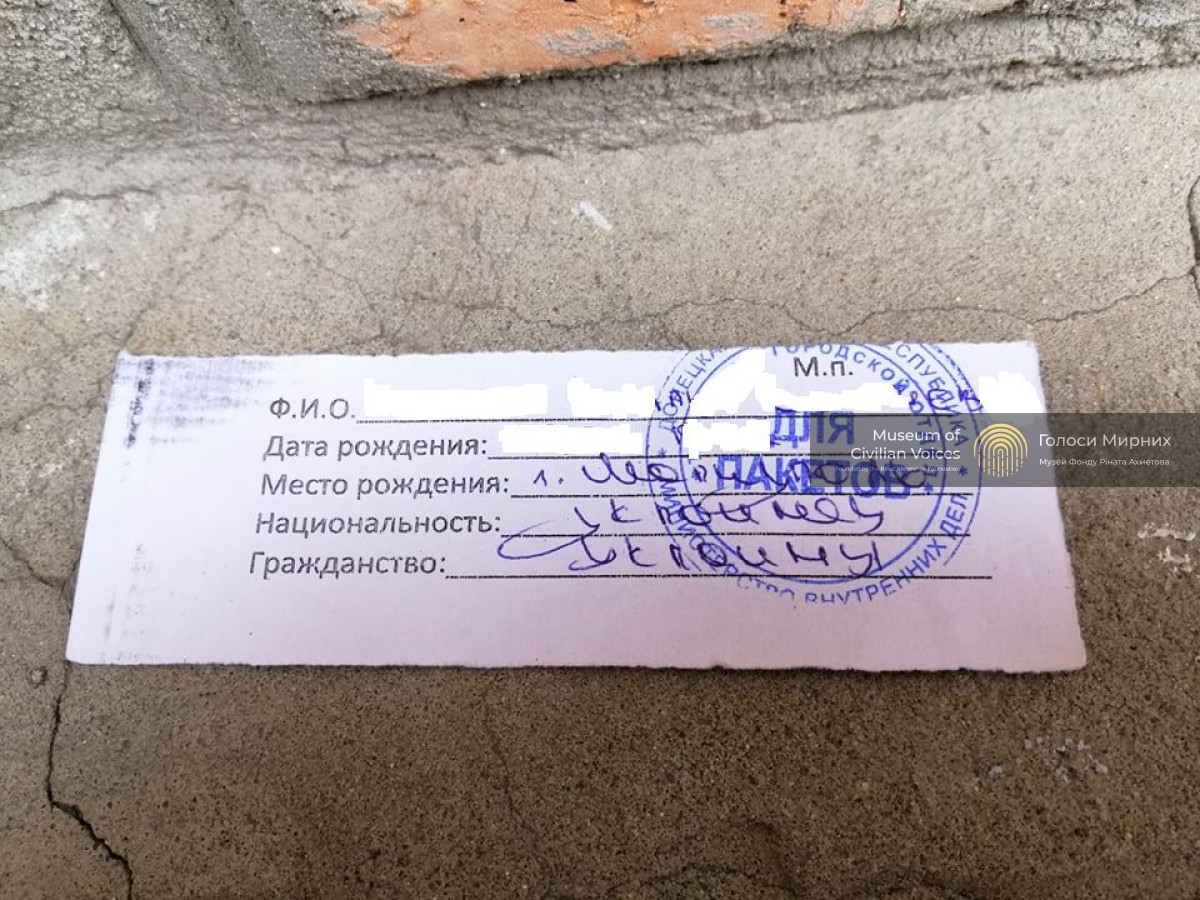

PS: the photo shows a piece of paper that is issued upon “filtration”.

My father’s parents are from a region that is part of the territory of Russia, but he was registered as a Ukrainian. Everyone is said to be registered that way. In words, they say about “denazification”, while in deeds, they themselves expand the circle of Ukrainians.

10 April 2022

Dozens of thousands of people from the besieged Mariupol are forced to flee the fighting, leaving for the temporarily occupied territories of Donetsk region and going further to Russia. Is it possible for them to return to Ukraine then? Yes, but it takes time and money.

We managed to test one of the travel routes first hand. It lasted nine days.

Notably, none of the officials in Ukraine has any reliable information about the ways to return. The situation keeps changing every next minute. Mostly for the worse. In particular, the control of people’s movements in the occupied territories is being tightened.

The starting point — 25 March. Several Russian soldiers armed with machine guns entered a bomb shelter in Livoberezhnyi district of Mariupol where my parents and more than a hundred other people had been staying day and night for about a month. The military gave them 30 minutes for collecting their things and ordered to get out and move on foot towards Sopino village, which was controlled by the occupying army.

Most of those exhausted people walked a way of about 10 kilometres. There, all of them were put on buses coming from the so-called DPR and taken to the village of Bezimenne, which was one of the hub settlements where IDPs from Mariupol were registered.

“Filtration”

For several weeks, Ukrainian politicians and journalists have been talking about the “filtration camps” on the other side of the frontline. What is that?

One of such camps is located in Bezimenne. A key transit hub was established there on the basis of a local school. Here part of the refugees are registered, provided with first medical aid, and fed with soup. The hub has a Wi-Fi connection and warm premises (as well as big military tents) for overnight staying.

But most importantly, one can meet former neighbours, colleagues and just acquaintances with whom to plan the next steps to take.

In this seaside village, people from the so-called DPR register only those who came by private transport. Duty cars or company cars are confiscated in favour of the unrecognized “(Donetsk People’s) Republic”. If a person left the city on foot, they have to wait for another bus and go to other places for registration: Donetsk, Dokuchayevsk, Starobesheve, Snizhne and others.

Travelling in the territory of the so-called DPR without the registration is prohibited.

Donetsk is the most popular destination as many people have acquaintances there. However, people have to wait in the queue for some four to seven days to go to the city.

Our parents did not plan to stay long in the occupied territories. That is why they headed off to where the nearest buses took them together with a large group of other travellers. It was a small coalmine town.

The registration process took about a day. There, they were questioned and asked to fill in their personal profile papers THREE TIMES (‘this is the procedure’). In addition, their fingerprints and palm prints were taken. Then, they were also photographed three times – one full-face picture and two pictures in profile. After that, they were given a paper with their basic data and a stamp from the Ministry of Internal Affairs of the so-called DPR.

They were additionally informed that the paper gives them the right to receive a passport of a citizen of the Russian Federation.

Immediately after leaving Mariupol, our parents were lucky enough to meet our relatives, who had left the city on a damaged car of their own. Our parents’ car, their garage and their house were destroyed by shellfire from Russian invaders. So, after registration, they agreed to meet at the “transit camp” in Bezimenne and go to Russia together.

They managed to return from the coalmine town to the Azov Sea coastal area only together with the “DPR” military, who earn a good bonus to their military allowance by providing a private transport/taxi service. Ordinary local taxi drivers do not go outside their hometowns due to the risk of mobilization and risk of being sent to the frontline.

Communication

This is the most important thing. Even if you got to the “DPR” territory with your phone and were able to charge it, it does not necessarily mean that you will be able to use it. Ukrainian telecom operators do not operate on this territory, and Wi-Fi points are far not everywhere — you have to ask. This is the only way to contact your relatives via some messengers.

Ukrainian cell phone network becomes available near the “border crossing point” with Russia in the roaming mode, and after entering the Russian Federation you can buy a SIM-card of the Russian mobile operator MTS. They are sold in a special kiosk placed in a large tent camp for refugees on the Russian side. They can be bought for Ukrainian currency – for UAH 200.

Communication is critical for coordination of actions with relatives, friends and volunteers throughout the travel route.

Transport

I had the opportunity to come to the border of Ukraine with Belarus by car, so we decided that the final destination for our parents’ trip should be in Brest region.

Planning of such a travel route – from the occupied territories via Russia and Belarus to Ukraine – and reaching of each of the planned destinations turned out to be the most difficult element of the operation.

To be honest, we were just lucky in many ways. The stars kept aligning for us in the most unexpected way. As many of our helping hands said, ‘With God’s help.’ But from a rational point of view, what helped us achieve the result was thorough preparations and support from the people we know in Ukraine, as well as those we do not know in Russia and Belarus, but people who understand the situation, who are conscious of the responsibility for the war and are ready to help to refugees from Ukraine.

Crossing of the border with Russia took them about two days, with overnight stays in our relatives’ car.

We insisted that our parents get off in Rostov-on-Don. Acting remotely from Ukraine, we found some volunteers who helped them with a temporary lodging and the purchase of tickets for a train to Minsk using an online app.

While waiting in Rostov, our parents had been watching and listening to the Russian military planes and helicopters for two days. For those who can take their family members out via the Baltic States and Poland, please note there is also a direct train from Rostov to Saint Petersburg.

The railway part of the route was supposed to be the simplest — you board the train, have a sleep, have some tea, and you get off. However, in practice, it turned out to be the most nerve-racking.

When boarding the train car, it turned out that crossing of the border between Russia and Belarus by train is formally prohibited for citizens of other countries. That is why the train chief gave them a paper notifying them that they will be fined for an amount from 2,000 to 5,000 Russian roubles when approaching the border. Moreover, they will be detrained in Smolensk, the last Russian railway station.

That was a strange situation as when you enter Russia you get a migration card that is common for both Russia and Belarus.

Our acquaintances, who took a similar route to get from Mariupol to Poland, could not buy the train tickets at the station ticket office at all (buying online allows you to hack the system though). At that time, there were also border control points on highways between Russia and Belarus (they were removed in the second half of March) where citizens of other countries were not allowed to pass, as formally there are no international border control points between these countries. For that reason, our acquaintances had to take a taxi to get to the so-called “three sisters” border crossing point on the border between Ukraine, Belarus and Russia. And from there, they went to Poland. That is both money and time consuming.

It should be noted that these aspects are not highlighted in any way in the online application from the Russian Railways, while the cashiers (in the ticket office) give some contradictory information. That is probably because the situation changes almost every day — we constantly followed the news and listened to information from our acquaintances from Belarus about the changes on the roads and at the border.

The train chief, who was in direct contact with the border guards, appeared to have the most accurate information. The border guards promised to let them through.

Our parents are retirees, that is why the border guards were easy on them. And after a visual contact in Smolensk, they left them in the train car, letting them enter the territory of Belarus even without a fine. Their major concern was that our parents do not go further to Poland.

If they were taken off the train, we had a backup option. Being in Ukraine, we managed to find people in Minsk remotely who were ready to go to Russian Smolensk or Novozybkov (another train from Rostov-on-Don goes through this station) and drive them to Minsk or to the border with Latvia by road.

After the train, our parents fell into the hands of people who are in fact involved in what is considered volunteering in Ukraine and Europe. However, in Belarus, such activity is prosecuted according to the legislation, and that is why they just became good acquaintances.

After a short break for rest, they headed off to the border between Belarus and Ukraine by car.

Finances

This is the shortest section of the story. Ukrainian bankcards could not be used either in the so-called DPR or in Russia. Ukrainian hryvnia in cash does not circulate in Russia and Belarus, and mobile banking applications cannot be opened without a VPN. That is why it is almost impossible to move through the territory of Russia without having some foreign currencies in cash (euro or dollar) or some financial support from local residents.

By the way, our parents exchanged a small amount of foreign currency at an exchange office at the rate of about 80 Russian roubles for one dollar. Locals asked to reimburse their expenses in roubles also based on the same exchange rate. That is why two compartment tickets for a sleeper train amounted to $300.

Documents

Many residents of Mariupol left their hometown almost empty-handed and not having a full package of documents with them.

It is hard to believe it now, but few people had their grab bags ready for evacuation. That is why many documents were gone completely and irreversibly.

According to our parents, those who made it to the “filtration camps” without their passports were asked the longest list of questions. They were questioned the last and with a special affinity. Most likely, the fact of the missing documents stripped them of the right for free movement within the pseudo-republics and in Russia. Perhaps, they were offered some internal documents issued by the so-called DPR and were then sent to some hinterlands in Russia by buses.

Those who had their national and foreign passports of Ukraine with them could move almost without any restrictions. Having your national passport with you, you can go to any neighbouring country, namely to Belarus, Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia and Georgia, but you cannot go freely further to any destination. For example, Georgians do not let you out without having your foreign passport with you. It is also difficult to board a plane with your internal Ukrainian passport to fly, for example, from Russia to Istanbul or from Georgia to Warsaw.

Ukrainian ID cards trigger a separate set of questions from Belarusian border guards, but there were still cases when they let Ukrainian citizens through with such a document.

Moreover, there are people who managed to escape from the territory of the so-called DPR to Russia with a driving licence and Diia mobile app — their passports burned in Mariupol together with the house. Now they are looking for an occasion to get out of Russia. There is hope that Ukrainian diplomats from countries bordering Russia could help with that.

Border crossing points and diplomatic support

We could not reach the hot line of the State Border Guard Service of Ukraine by phone, but an online map on its website can be trusted. It shows that two border crossing points are now operational on the border between Ukraine and Belarus. As practice has shown, meeting our parents on the Belarusian-Ukrainian border was a risky idea, as the real situation on site is quite obscure.

Communication with our diplomats was of little help. Until the last moment, we were not even sure that our parents would be able to travel from Russia to Belarus. Other people’s practice prompted that this was possible, but a written response from the Ukrainian embassy in Belarus stated that the only way for Ukrainian citizens to legally enter the territory of Belarus was through Minsk airport. Further clarifying questions remained unanswered.

A telephone call to the embassy’s hot line ended in an even bigger fiasco. On the other end of the line, when they heard that our parents were still in Rostov, they advised us to call the nearest embassy — in Georgia. The fact that Ukrainian citizens intended to go to Belarus was not a worthy argument for the development of dialogue.

Even after getting our contacts involved and talking to our diplomats in Minsk again, we received answers that did not quite coincide with practice.

While our parents’ entire journey was full of unexpected turns, the biggest surprise for my brother and me awaited us 80 kilometres from the state border.

We were stopped at the National Police checkpoint and actually persuaded to turn around with the words that the border crossing point with Belarus in Domanovo does not work — a neutral stripe was dug up there. Thus, we had to send our parents to Poland.

A call to the Belarusians, those who brought our parents to the border, helped us. It turned out that Belarusian border guards had already let them through to the Ukrainian side.

For our parents, those turned out to be the most difficult 1.5 kilometres of the route: going on foot through the snow and across the defence line.

More than four hours of waiting, check-ups by Ukrainian special services and finally a long-awaited meeting at the empty Ukrainian border crossing point.

A few months ago, life was probably in full action here. Now – locals from nearby villages show up on rear occasions to buy some food and hot-dogs in the only shop that is open there. A shopkeeper told us that we were the second ones that day, picking up our relatives there. And this does not happen every day.

My brother and I drank some hot tea, bought our parents warm socks and a small bottle of cognac for them to warm up and get rid of stress after a hard journey.

Instead of an Epilogue

This special operation showed a great number of gaps and challenges encountered by Ukrainian citizens who forcedly had to be on the other side of the line of demarcation.

There are no “green corridors”, no transport and no telecommunications for our refugees to the east of Mariupol. Most people can only rely on their own efforts, wits and resources.

It is possible to get to Ukraine via Russia, but I would recommend this way only to those who are ready to take up such trials and challenges morally, financially, organizationally and document-wise.

Unfortunately, for those who forcedly travelled to the temporarily uncontrolled territories, the state does not have a ready-made recipe as to how and where they should be going further. Family members ready to help and take back their parents, friends and acquaintances, who got to the so-called DPR and Russia, do not have a recipe either.

Very often, people do not even know that their relatives were able to get out of the besieged city and are alive. And the plan of movements has to be changed several times a day.

As a result, thousands of Mariupol residents “go with the stream” created by Russians and are not able to get out of this stream. And they only manage to reach Ukraine by phone when they are in Tula or Penza.

Or, what is worse, after weeks of living in cold bomb shelters, without food and under constant shelling, some of them are ready not just to receive food from Kadyrov’s mercenaries and “DPR” soldiers, but also to call them good guys. In spite of the fact that the latter deprived them of their flats, cars and any means of subsistence, and deprived hundreds of thousands of their fellow Mariupol residents of their lives and health.

When quoting a story, a reference to the source – the Museum of Civilian Voices of the Rinat Akhmetov Foundation – is mandatory, as follows:

The Museum of Civilian Voices of the Rinat Akhmetov Foundation https://civilvoicesmuseum.org/